13 Fascinating Facts About Festac 77 You Would Appreciate If You Were Born After 1977

Festac ’77, also known as the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, was a cultural and historical milestone for Africa and the global Black community. Held from January 15 to February 12, 1977, in Lagos, Nigeria, it celebrated the artistic, intellectual, and cultural contributions of Africa and its diaspora. Here’s a closer look at 15 intriguing aspects of this iconic event.

It Was the Largest Gathering of Black and African Cultures

Festac ’77 was a monumental event, bringing together over 17,000 artists, performers, and scholars from 56 African countries and the diaspora. It showcased Black and African cultures’ sheer diversity and richness, uniting participants through art, music, dance, and literature. No other festival before or since has matched its scale and cultural significance.

A Long-Delayed Dream

The idea for Festac ’77 originated after the first festival in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966. It was meant to be a periodic event celebrating Pan-Africanism and Black culture. Nigeria was selected to host the second edition in 1970, but the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) forced a delay. After several years of planning and rescheduling, the festival finally occurred in 1977.

The Mask as a Symbol

The official emblem of Festac ’77 was a replica of the famous Benin Ivory Mask, one of Africa’s most iconic art pieces. Erhabor Emokpae of Benin crafted the replica, representing the artistic sophistication of ancient African civilizations. During the festival, it adorned banners, posters, and sculptures.

Nigeria as Host Nation

Nigeria was chosen to host Festac ’77 due to its cultural richness and growing political influence. By the 1970s, Nigeria was an economic powerhouse in Africa, buoyed by its oil wealth. Hosting the festival allowed Nigeria to show its leadership on the continent and its dedication to celebrating Black culture worldwide.

The Building of Festac Town

To host the influx of participants, the Nigerian government built Festac Town, a massive housing estate in Lagos. It was designed as a modern residential area featuring over 5,000 housing units, schools, hospitals, and recreational facilities. After the festival, Festac Town became a thriving Lagos suburb and remains a cultural and historical landmark.

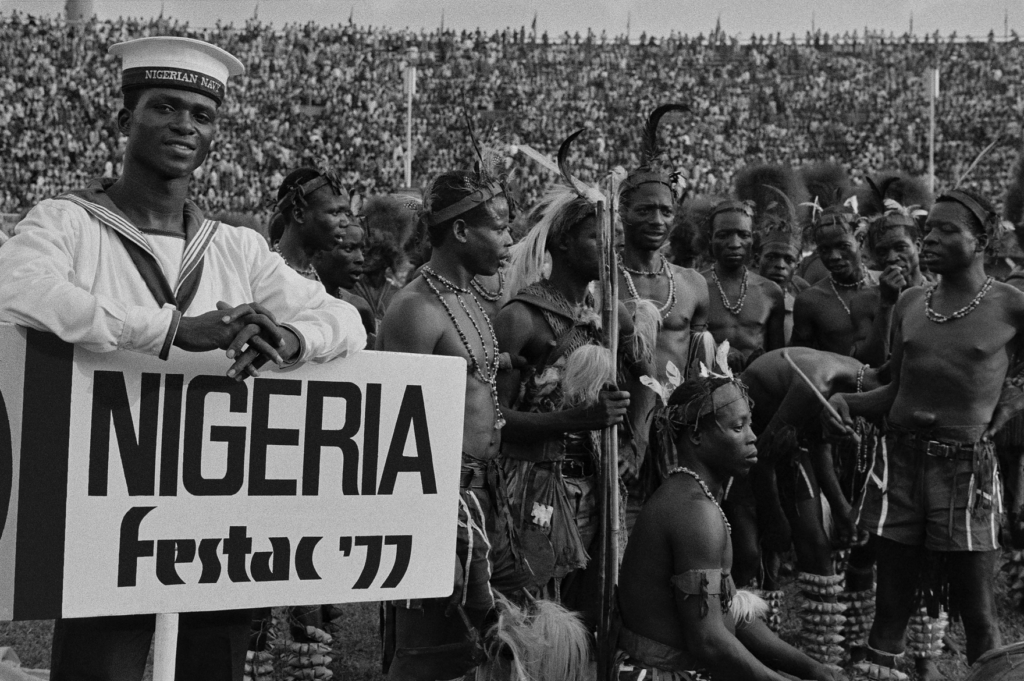

The Opening Ceremony at the National Stadium

The festival began with an extravagant opening ceremony at the National Stadium in Surulere, Lagos. It featured a colorful parade of participating nations, cultural performances, and speeches. The spectacle emphasized the festival’s themes of unity and pride, with thousands of spectators witnessing the grand celebration.

Showcasing African Arts and Culture

Festac ’77 was a massive platform for African art, music, literature, and performance. Artists displayed traditional and contemporary works, while dancers and musicians showcased diverse styles across the continent. The event celebrated everything from film, drama, dance, books, paintings, and musical instruments.

Participation by Global Icons

Some of the biggest names in African and Black culture participated in Festac ’77. South African musician Miriam Makeba, American singer Stevie Wonder, and literary figures like Wole Soyinka attended, sharing their talents and insights. Their involvement underscored the global impact of Black and African culture.

Promotion of African Unity

Festac ’77 was deeply rooted in the spirit of Pan-Africanism, promoting unity among African nations and the diaspora. The festival reinforced the idea that despite differences in language and traditions, Black and African people share a common heritage and destiny. It served as a call for solidarity and pride in the face of colonial histories.

Music as the Soul of the Festival

Music played a central role in Festac ’77, with performances ranging from traditional African drumming to reggae and jazz. However, the festival also had its controversies. Nigerian Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti boycotted the event, criticizing the government’s misuse of funds, which cost about half a billion dollars. Despite this, music remained a unifying and electrifying element throughout the festival.

Historical and Educational Forums

Beyond the performances, Festac ’77 also served as a platform for intellectual exchange. Scholars, historians, and cultural experts held seminars and discussions on African history, colonization, and the future of Black and African cultures. These forums explored the absence of intellectual independence exhibited by the Third World countries who still sought expertise from the colonizers while feigning independence to themselves and others.

A Celebration of Diaspora Contributions

Festac ’77 wasn’t just for Africans on the continent—it included vibrant contributions from the diaspora. Caribbean participants performed traditional dances, and African-American artists shared jazz and soul music. These performances highlighted how African culture has evolved and thrived globally despite displacement and adversity.

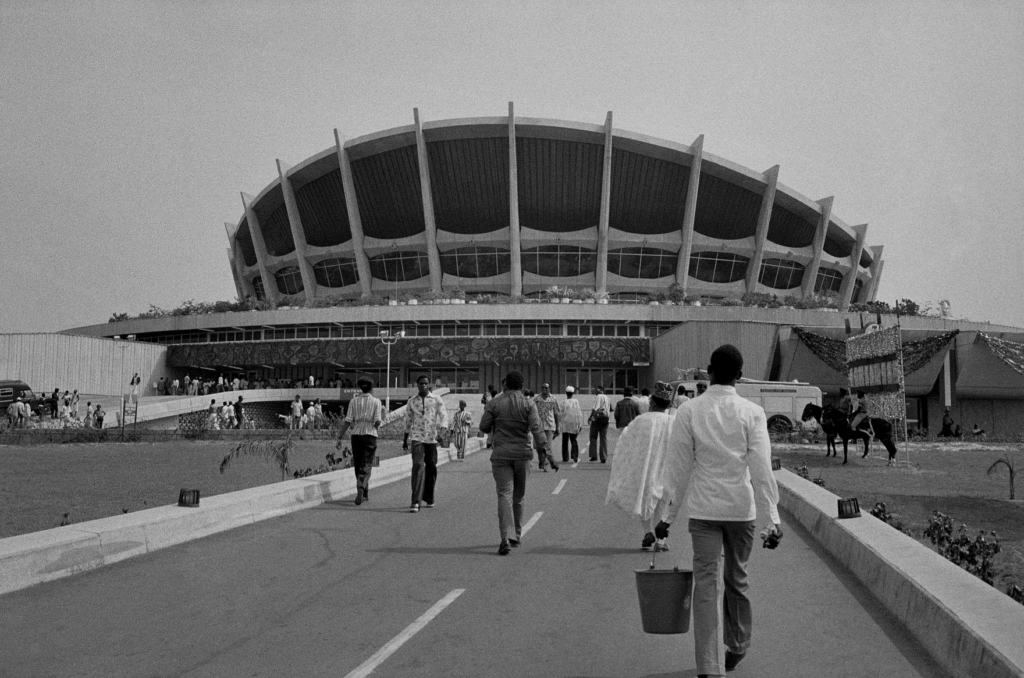

Legacy and Influence

The impact of Festac ’77 extended far beyond its month-long run. It inspired cultural festivals across Africa and the diaspora, fostering a renewed identity and pride among Black and African communities. Institutions like Festac Town and the National Theatre in Lagos remain enduring symbols of its legacy.